Wyatt is designed to be a modular and testable framework for developing robot code. It provides structures for unit testing your robot code, as well as a framework for abstracting hardware to make it easy to adapt your code to whichever system you are running on.

You can check out all of the generated project documentation here. If you’re only interested in learning how to set up and use this framework for your own projects, you can jump to the installation section.

Motivations

The primary motivation behind this project was to create a framework for small robotic systems that allowed for easy unit testing and proper test-driven development. We also wanted to provide a command-based framework similar to the one in WPILib (used in the FIRST robotics competition), but in a lighter-weight fashion. The framework needed to be able to run on a small computer like the Raspberry Pi, and provide excellent performance so that it can be used in a robot to solve a challenge that requires pseudo-realtime response to sensors.

We were so driven to make robots testable due in part to WPI’s Robotics Engineering core courses. Students in the robotics program are required to take a software engineering course as part of their studies, but due to the limited time afforded to them in the robotics courses and the lack of a good framework, robot code is often not functionally tested except for on the field. Students have no guarantee or even a good idea of whether or not their robot will reliably perform on the field, because they have no way of testing portions of their robot at a time. They can only test the whole thing together. We wanted to help with that by building this framework that allows students to build their robot code using the test-driven development techniques that they learn in software engineering. Our hope is that students will use this framework to build more reliable robots and put their software engineering skills to good use.

Takeaways

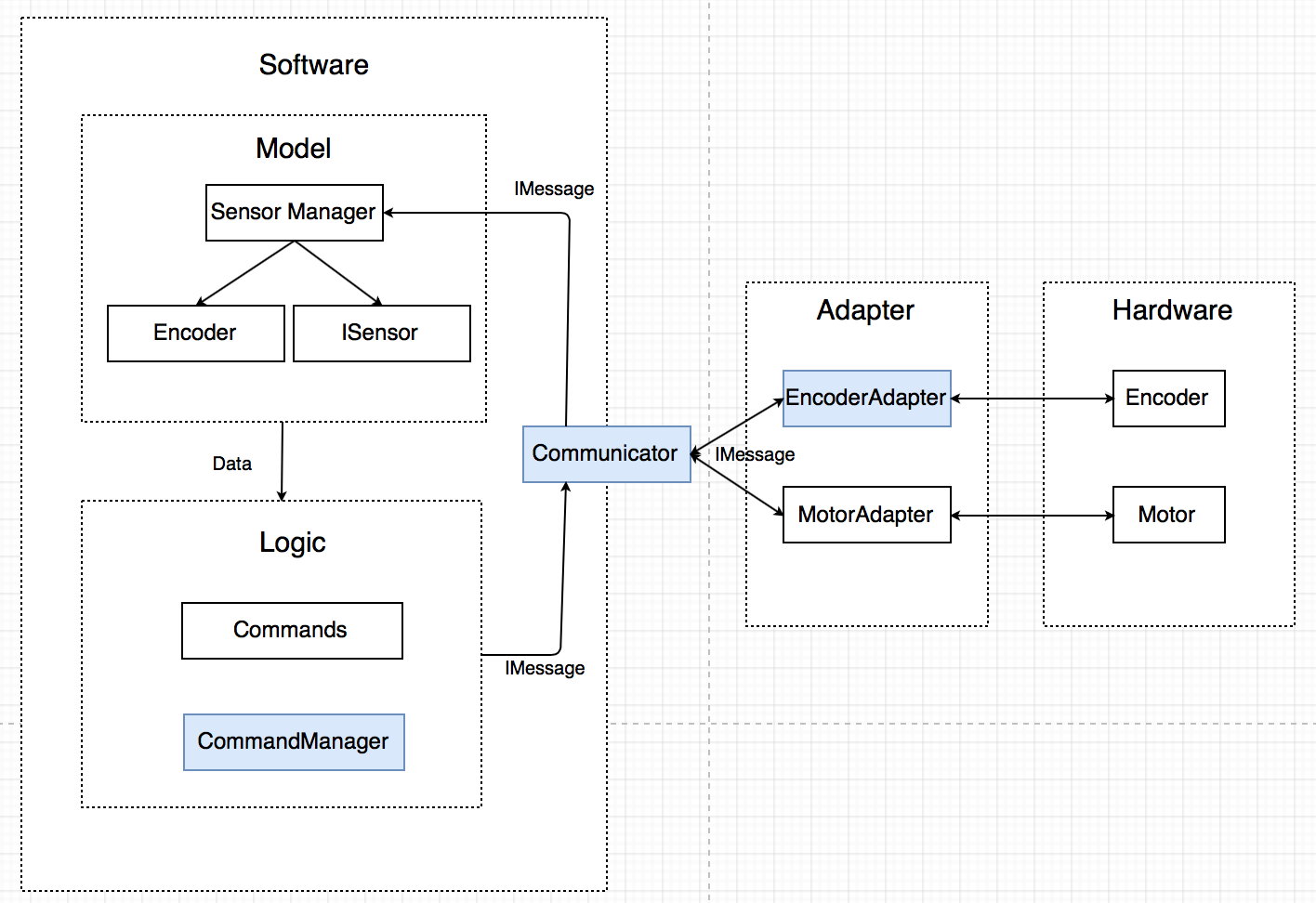

The major takeaway from this project was the concept of hardware abstraction. Early on in the project we identified hardware dependencies as a major blocker to testable code. To work through this, the code structure we designed abstracted away all of the hardware. A picture of this diagram is included below.

To abstract away the hardware, we created a set of adapter classes that interface directly with the hardware and return a set of standardized messages. For example, the EncoderAdapter class reads the encoder and uses the robot’s geometry to determine the speed of a wheel in cm/s. It then returns a message containing that data. The MotorAdapter class receives a messages with a specified speed in cm/s and converts it to the proper signal to send to the actual motor hardware.

The purpose of this abstraction is to decouple the program’s logic from the hardware specifics. Since standardized messages are sent and received the software does not have to know about the hardware. For instance, you set a specified wheel velocity and the adapters figure out how to command the motors to achieve that velocity.

Installation

Wyatt will run on Linux or Mac. Unfortunately we don’t support Windows, though you can set up the project with Bash for Windows in the latest versions of Windows 10. It may also be possible to configure the project using CLion on Windows, but that has not been tested. For each of the supported platforms, installation instructions are provided below. If you are working on a Raspberry Pi, do not follow the Linux directions. Skip to the Raspberry Pi directions, as it requires different setup steps.

Linux

This guide is written assuming you are using a Debian-based platform, with the apt package manager. You will need to first install a few dependencies, namely cmake, clang, doxygen, and lcov. You will then need to clone the git repository from the official GitHub repository. You can build this project using either clang or gcc, but we developed it using clang. If you don’t want to use clang, omit the export lines from the bash snippet below.

sudo apt-get install cmake build-essential clang doxygen lcov git

git clone https://github.com/arthurlockman/wyatt.git

export CC=/usr/bin/clang

export CXX=/usr/bin/clang++

cd wyatt

mkdir build

cd build

cmake ..

make -j8

Raspberry Pi

The Raspberry Pi is a Linux platform, but it requires a few extra steps to make it work properly with the Wyatt framework. The main difference is that you will need to jump through a few extra hoops to get it to build with cmake and clang. First, install cmake, clang, and the other dependencies.

sudo apt-get install cmake build-essential clang-3.9 doxygen lcov git

ln -s /usr/bin/clang-3.9 /usr/bin/clang

ln -s /usr/bin/clang++-3.9 /usr/bin/clang++

Next, you will need to create a file so that cmake can find the WiringPi and WiringSerial libraries on the Raspberry Pi. Copy the following into your cmake module folder, which usually looks something like /usr/share/cmake-3.x/Modules:

find_library(WIRINGPI_LIBRARIES NAMES wiringPi)

find_path(WIRINGPI_INCLUDE_DIRS NAMES wiringPi.h)

include(FindPackageHandleStandardArgs)

find_package_handle_standard_args(wiringPi DEFAULT_MSG WIRINGPI_LIBRARIES WIRINGPI_INCLUDE_DIRS)

Now, you can clone the project and complete the first build.

git clone https://github.com/arthurlockman/wyatt.git

export CC=/usr/bin/clang

export CXX=/usr/bin/clang++

cd wyatt

mkdir build

cd build

cmake ..

make -j8

macOS Sierra and Newer

This guide is written assuming you are using macOS Sierra or newer. If you are on an older platform you may need to modify these instructions. In order to start the installation, you will need to install Homebrew from the official website. Once that is done, you need to install some dependencies, clone the git repository, and complete the initial build. If you have Xcode installed already, then you likely can skip installing clang using homebrew.

brew install cmake clang doxygen lcov git

git clone https://github.com/arthurlockman/wyatt.git

export CC=/usr/bin/clang

export CXX=/usr/bin/clang++

cd wyatt

mkdir build

cd build

cmake ..

make -j8

Assuming you have no errors in any of the install steps above, you are now ready to go! Skip down to the getting started guide to learn how to set up your own project, and how to build and run the provided example project.

Getting Started

This section details how to build, run, and deploy your project to continuous integration services.

Building

The project is built through cmake. We have provided an easy script to allow you to build and run your code. In the project root, simply run the ./deploy.sh script to build and run your code. If you need to clean the build directory and do a complete rebuild, run ./deploy.sh -c. This will delete the build directory, rebuild complete, and run your project.

Running

If you wish to simply run your code without building you need to run the build wyatt executable in the build directory. If you are using the standard build folder for building, you can run your project with this command:

./build/src/wyatt

Running Tests

To run your suite of unit tests built with Catch, you need to build your project and then run the testing executable in the project build directory.

cd build

cmake ..

make

cd ..

./build/test/wyatt_test

Alternatively, you can run tests with ctest (cmake’s built-in testing library):

cd build

cmake ..

make

ctest -V

Building Documentation

Building documentation with Doxygen is handled through cmake. Simply run the following commands to build the Doxygen report and place it in the /docs/html folder.

cd build

cmake ..

make doc

make doc install

Code Coverage Reporting

Code coverage reporting is handled with ctest and lcov. Lcov handles generating the coverage report, and compiles the report in a format that can be understood by online code coverage reporting systems. We used codecov.io for this project, but you can use any service that can accept output from lcov. To build your own HTML version of the code coverage report:

cd build

cmake ..

make

make Wyatt_coverage

Assuming no errors, your code coverage report can be found by opening ./build/coverage/index.html in your project root.

Deploying to CI

This project is already successfully deployed to Travis CI for continuous integration testing and deployment. To deploy your own copy of this project to Travis or a similar CI provider, you will need to modify the .travis.yml file in the project root to suit your own project. This file handles building the project on Travis, and pushing the code coverage reports to Codecov. If you use Travis and Codecov to build your project, then you likely do not need to make any modifications to the .travis.yml file at all, and can use it as-is for your CI builds. There is also a config file for codecov.io in the project root, but if you don’t need any modifications past what we’ve already customized then you can likely leave that file alone.

Creating Projects

This section details how to create your own projects, and how the example project included in the framework is laid out.

Robot Structure

All of the robot code for the example project is in the Robot.cpp and Robot.h files. The Robot.cpp file contains two methods: the constructor and the run method. The constructor is used to initialize all of the robot components, and the run method is called in the program main() loop. You can choose to either structure your code in here sequentially or as a state machine, the framework will support either. Note that the main() method is not called in unit tests. For tests, you need to specify your own methods (detailed in the testing section.

Command Framework

Robots built using Wyatt should use the built-in command framework. This framework allows for different robot tasks to be run in parallel in a repeatable manner. To start using the command framework, you need to first initialize the CommandManager class, which handles running commands. Then, to run a command you need to initialize it and pass it off to the command manager.

CommandManager* commander = new CommandManager();

double radius = 60; // cm

int duration_ms = 10000; // ms

double rotationRate = 2 * 3.14159 / (duration_ms / 1000.0); // 1 rotation in X seconds

Command* driveArc = new DriveRobotCommand(

this->communicator,

this->leftEncoderSensor,

this->rightEncoderSensor,

radius,

rotationRate,

duration_ms,

WHEEL_DIAMETER,

DRIVETRAIN_DIAMETER);

this->commander->runCommand(driveArc);

while(!driveArc->isFinished()); //wait for command to finish

The snippet above creates a command manager and runs a DriveRobotCommand. Note that the command framework does not handle commands that need to run in sequence. To do that you need to use a spinlock like in the snippet above to wait for your first command to finish, and then queue another one to run. By default all commands are run in parallel.

Testing

One of the major goals of this project was to create a framework for a robot that was testable and verifiable. The majority of code written by WPI RBE students is spaghetti code: it works well enough to get the lab report done but is not extendable, maintainable, or even correct in some cases. Furthermore, students must always be the in RBE lab to test their code. The code is typically tied to the hardware in such a way that they can’t build and execute it on their own machines. As a result, development bottlenecked by a single robot and by the time it takes to upload, setup, and deploy the robot.

Unit Test

In software engineering, unit tests are used to verify ‘units’ of code, prove that they work the first time, and check that a ‘unit’ of code still works after changes to the system. Moreover, good unit tests should check standard behavior as well as corner cases and exceptions.

A unit is a scoped section of code that has a defined input and output. In object-oriented programming, a unit is typically a class.

To unit test a piece of code, one creates and gives as input some mock data to a unit and requires that a specific output is created.

Examples

Consider a java class that performs various algebraic functions.

class Algebra {

int add(int a, int b);

int subtract(int a, int b);

int multiply(int a, int b);

double divide(int num, int den);

}

Unit tests check expected behavior but should also check corner cases and exceptions.

// Check standard division

@Test

public void testSumLargeNumbers() {

Algebra alg = new Algebra();

assert(alg.divide(1, 2) == 0.5);

}

// Check dividing zero by an integer results in zero

@Test

public void testSumLargeNumbers() {

Algebra alg = new Algebra();

assert(alg.divide(0, 2) == 0.0);

}

// Check dividing by zero results in DivideByZeroException

@Test

public void testSumLargeNumbers() {

Algebra alg = new Algebra();

try{

alg.divide(1, 0);

fail(); // Fail if no exception thrown

} catch(DivideByZeroException) {

pass(); // Pass if expected exception

} catch(Exception) {

fail(); // Fail otherwise

}

}

// Check dividing zero by zero results in DivideByZeroException

@Test

public void testSumLargeNumbers() {

Algebra alg = new Algebra();

try{

alg.divide(0, 0);

fail(); // Fail if no exception thrown

} catch(DivideByZeroException) {

pass(); // Pass if expected exception

} catch(Exception) {

fail(); // Fail otherwise

}

}

Dependency Injection

Dependency injection is a software engineering principle used to create loosely-coupled and easily testable code. Dependency injection is the process of injecting dependencies into units of code through their constructors. This is best demonstrated with an example. Consider this command class below.

class DriveMotorSpeedCommand: public Command {

public:

DriveMotorSpeedCommand(Motor* motor, Encoder* encoder, int speed);

}

The dependencies for this class are the encoder and the motor objects. The command is dependent on the encoder to get the most current speed reading and dependent on the motor object to control the motor.

With dependency injection, unit testing becomes a breeze. In the unit test, one can create mock objects for the motor and encoder that have specific behaviors. One can use this specific behavior to generate a specified set of input (in this case the current motor speed from the encoder) and check that a specific output is generated (the motor is driven in a particular direction).

TEST_CASE("DriveMotorSpeedCommand") {

Motor* mockMotor = new MockMotor(); // MockMotor extends Motor

Encoder* encoder = new MockEncoder(); // MockEncoder extends Encoder

// Have the encoder read a speed of zero

encoder.setValue(0);

// Drive the wheel at 1 cm/s

DriveMotorSpeedCommand(mockMotor, mockEncoder, 1);

// Check that the motor is now being driven forwards

REQUIRE(mockMotor.power() > 0);

}

Dependency injection is critical for creating testable code, even on a hardware-integrated system. Notice how the hardware is abstracted away in the unit test.

Now the code can be written and tested without a robot present!